Old Athletic Field

The Old Athletic Field is central to the history of sports and entertainment in Stillwater. From horse racing and circuses to professional baseball and high school football, it has hosted the city’s recreational life for more than 150 years. Notably, it was the site of Stillwater’s short-lived minor league professional ballclub starring the first Black professional baseball player in the United States, Bud Fowler. Over the years, it has had many names, including St. Croix Park, Aurora Park, Athletic Park, and Athletic Field.

Early History

Like the rest of Stillwater, the Old Athletic Field land was the home of the Dakota people and their ancestors for thousands of years. In 1837, the Dakota ceded much of the St. Croix Valley to the United States in a treaty. Ten years later, an early U.S. government survey crew was recording the land around the small village of Stillwater. That November 8, surveyors traveled north along the future line of Sixth Avenue. The surveyors noted that the land in the general area was rolling, with second-rate soil and a scattering of oak and aspen trees. From 1849 through 1854, the future Athletic Field land changed hands several times before being purchased by prominent lumberman Isaac Staples. In 1857, Staples and his partners divided the land into blocks and lots, naming the neighborhood Hersey, Staples & Company’s Addition to Stillwater. Today’s Old Athletic Field occupies two blocks of this neighborhood, and has been used for recreation since Staples’ time.[1]

1865-1872: Horse Racing and the County Fair

In August 1865, a few months after the Civil War, the Stillwater Messenger reported that a group of Stillwater citizens intended to create a racecourse about a mile south of the city. “We believe the ground has been selected and surveyed, and a sufficient amount raised to defray the expense of clearing up and preparing the ground.” By the following June, the track was apparently completed. That summer, the newspaper expressed displeasure at young people causing disruptions by racing horses on Pine Street near the South Hill school and homes. The Messenger reminded readers that there was “a circular track about a half mile distant from our school houses and churches, constructed for the special purpose of horse-racing and boisterous conduct.”[2]

Resident Paul Caplazi recalled the horse track decades later, describing a location including the present Old Athletic Field land but also extending about a half block to the north and west:

Orleans St. was the end of the south turn of the race track. 5th Ave. was the track stretch. The north turn ran back of the Ed. Staples house on the N.E. corner of 6th Ave. and Burlington St.

The end of the north turn was a little south of Hancock. The home stretch was about the middle of the block between 6th Ave. and First St. The Judges stand was about Marsh St. and across on 5th Ave. was a big rock which was used for the quarter pole.[3]

In 1871, five years after the initial creation of the South Hill race course, Stillwater saw a number of changes in horse racing. In January, the Stillwater Gazette described a one-mile race course being created on the frozen St. Croix River across from the city. That summer, William Rutherford announced that he would build a racetrack on his land west of Stillwater. It may have seemed that the days of racing on the South Hill were over.[4]

The first Washington County Fair was held in 1871 in Cottage Grove, but its organizers noted that there was no guarantee that it would return there. The next year, Stillwater wanted the fair, and a group of prominent business leaders devised “liberal inducements” to convince fair organizers to select a site in the area. After considering various sites, the Stillwater group determined that the “old race course” was the best option, and the Agricultural Society agreed to bring the next fair to Stillwater.[5]

Building the new fairgrounds was itself a race against time. Decisions and construction continued nearly until opening day, but the 1872 fair was apparently a success. Among the highlights was Stillwater’s recently-formed fire department, whose members paraded “in gorgeous array” along with “their machinery bright as the sun.” The Stillwater Band performed throughout the fair, and University of Minnesota president William Watts Folwell gave an address. Exhibits were displayed in “commodious buildings,” and the fair used generous donated funds to provide prizes to the winners.[6]

Soon after the fair ended, its local boosters decided to purchase new and much larger grounds west of town, in the hills above Lily Lake. The new location became known as the Lily Lake Driving Park, and in following decades it was the main location for county fairs and horse racing. The old grounds on the South Hill were soon used for new activities including circuses and baseball.[7]

1873-1883: “St. Croix Park”: Early Baseball and Other Recreation

After county fairs and most racing moved to Lily Lake, the old race track was used for occasional shooting sport events. In July 1873, the Sportsman’s Club’s 28 members planned a shooting match with “real live pigeons.” Another match “for turkeys and chickens” followed on December 23-24. A third event was held in July 1874 with “a good many in attendance as lookers on.” At least one horse race was scheduled for the old track, in July 1874 “for a saddle worth about six dollars, between Luke Burns’ horse and Newman’s colt.”[8]

But the grounds became best known for baseball.

Stillwater’s first team was the St. Croix Base Ball Club, organized in 1867 during a wave of popularity for baseball in Minnesota. In their early years, the St. Croixs’ field locations included the South Hill near downtown, the Baytown Flats (probably near the present-day Andersen and Xcel plants), Carli’s Field on the north side of Stillwater, and the new driving park above Lily Lake.[9]

By 1876, baseball had become even more popular and was replacing horse racing in the hearts of Stillwater’s residents. That spring, the Messenger noted: “Our athletic young men are taking more interest in base ball matters this season than ever before.” Building on that excitement, the St. Croix team moved to the old race track grounds, which they named “St. Croix Park.” The Messenger predicted the move “will furnish the club with better quarters than they ever had before. Some fine exhibition of our national game may be looked for by our citizens this season.” In August, the newspaper was even more enthusiastic:

The game of base ball is more popular in this county today than ever before, and as an athletic sport surpasses any thing ever introduced. It is to some extent taking the place of horse racing as an out-door sport, and it is not impossible that the latter will in time give place to the former. Certainly baseball furnishes more amusement and excitement than horse racing, and is less expensive and demoralizing.

Our citizens have manifested an unusual interest in the game, and at last proper grounds have been provided and fenced and an ampitheatre erected, so that the game may be played and witnessed with a comparative degree of comfort. These grounds, situate on the old race-course south of the city, will be formally opened next week by a game between the St. Croix club and a nine from abroad, the arrangements for which have not been perfected. The entrance fee will probably be 25 cents, and we can assure our readers that they will feel richly repaid for their investment.[10]

Two months later, the St. Croixs had one of their most exciting moments. They challenged the national champion Chicago White Stockings (later known as the Chicago Cubs) to a game in Stillwater during one of Chicago’s road trips. The Chicago team featured future hall of famers Adrian Anson and Albert Spalding. Stillwater lost to the champions, 18-3, but the local fans enjoyed what the Messenger called “the finest game of ball ever played in this city.”[11]

St. Croix Park wasn’t only used for sports. Another 1876 highlight was a visit by Cooper, Bailey & Co.’s circus in July. Like other circuses of the era, it featured a variety of animals; the circus promoted what it claimed were the only trained elephants, sea lions, and giraffes in America. The circus’ ad emphasized its global nature, with “every nation upon earth represented.” Circuses were major productions: the Cooper-Bailey show traveled in 43 rail cars and employed a private detective force “to protect our patrons from imposition, sharks, thieves, etc.”[12]

The next summer, a Prof. Schmotter promised that on July 3, St. Croix Park would see “the finest pyrotechnic display ever witnessed in Minnesota, being a facsimile of the sublime display at Philadelphia a year ago.” The following month, a circus set up “on the old fair grounds opposite base ball grounds.” This was probably across Orleans Street from the ballpark, since the Messenger claimed the circus had moved just outside city limits due to the city “imposing an exorbitant license fee.” Another circus this location to avoid paying city fees in 1878. The city may have eliminated the fee, since circuses returned to the baseball grounds in 1879 and 1883. The Messenger described the 1883 show:

W.W. Cole’s circus and menagerie gave two fine exhibitions on the base ball grounds in this city Monday afternoon and evening, the attendance being estimated at upward of 8,000 persons. Every feature of the performances was first-class and although several features advertised were not furnished there was less cause for complaint than is usually the case. The company was composed of ladies and gentlemen and if there were thieves connected with it they kept mighty shady here.”[13]

That summer, Stillwater also watched its baseball team’s remarkable run, turning around from a terrible start to end the season as champions. The city’s fans responded to the excitement: a late-season crowd of nearly 800 people watched a game on September 16. Soon after the season ended, Stillwater was contemplating a major advance in baseball and civic pride: a professional team.[14]

1884: Bud Fowler and Stillwater’s Professional Baseball Era

Baseball’s professional Northwestern League began in 1883 and expanded into Minnesota in 1884 by adding teams in Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Stillwater. For several years, teams in some of Minnesota’s larger cities had been gradually transitioning from amateur to semi-professional (a mix of amateur and paid players). Now, the three Northwestern League teams would be fully professional, with all players being paid. The Northwestern was considered to be a premier minor league due to its affiliation with the National League and American Association. In March 1884, the Stillwater club announced its new roster, which included no St. Croix Valley residents and only one Minnesotan. Most players were from the East Coast or Chicago. Stillwater was the smallest city in the league.[15]

One of the team’s most successful players—and certainly the most historically significant—was John Jackson, who played under the name Bud Fowler. Fowler had grown up in the Cooperstown, N.Y. area before beginning a baseball career that would take him to teams across the East, Midwest, and Southwest. In 1878 he broke a color barrier as the first Black professional baseball player, pitching three games to replace an injured pitcher in Lynn, Massachusetts. After Lynn’s regular pitcher recovered, Fowler returned to semi-professional teams. Six years later, however, he was recruited to play for Stillwater’s new professional team.[16]

While the team’s management spent the winter recruiting a roster of players, it also needed to make plans for a suitable ballpark. The company initially considered constructing a ballpark near the river, in the Northwestern Manufacturing Company’s former brick yard (the present-day parking lot behind River Market and River Siren Brewery). Though a riverfront park was appealing, and it was thought that the club could afford rent for the land, the parcel was ultimately deemed too narrow. Instead, the club decided to build a new park adjacent to and immediately south of the existing ballpark.[17]

The St. Paul Daily Globe described the new park:

The new baseball grounds on sixth Avenue, are nearing completion. The location is an excellent one, as the grounds, except in a case of a very heavy rain, could not be better than they are. The field is perfectly smooth, with a slight decline to the East. The grand stand, which will seat some 500 spectators, and will be admirably fitted up with seats, is at the south side, giving an excellent view of the games. The whole grounds are enclosed by a tight board fence, some ten feet high, which will trouble the gammins to get over, as none other would be mean enough to try.[18]

The new park was 450 by 400 feet, and based on this size probably extended east across Fifth Avenue. The outfield fence was 350 feet from home plate. A new telegraph line was constructed into the ballpark “so as to avoid delay in the transmission of messages announcing the result of league games.”[19]

The season began on May 1, with several weeks of away games before the home opener on June 9. Stillwater had a disastrous start, losing its first 16 games before finally winning on May 24 at Fort Wayne, Indiana. The Fort Wayne Morning Journal attributed its team’s loss to Bud Fowler’s pitching. Stillwater fans naturally had a more positive take, and Fowler “was presented with a $10 bill and a suit of clothes” in recognition of his central role in the team’s first victory. Stillwater’s fortunes improved in the following weeks, leading up to the long-awaited home opener. Stillwater lost that game to Minneapolis, and had a mixed record for most of the summer. Fowler played a variety of positions for Stillwater: pitcher, catcher, infield and outfield. He accumulated a .302 batting average and led the league in hits. Fowler’s performance made him a Stillwater fan favorite, but throughout his pioneering career he dealt with outright racism and unusually rough on-field conduct from opposing teams.[20]

When Bud Fowler wasn’t playing baseball, he worked as a Stillwater barber and lived in lodging associated with the Live and Let Live restaurant owned by William Humphries, a fellow Black resident of Stillwater.[21]

The Northwestern League and its clubs ran into increasing financial difficulties as the summer progressed. The Stillwater and Fort Wayne clubs folded on August 4, followed by several other teams. It was the end of Stillwater’s brief, ambitious era of professional baseball. The next season, Bud Fowler moved on to a team in Iowa, the next of many stops in a baseball career that spanned more than three decades. Held back by baseball’s increasing segregation, Fowler was never able to play in the major leagues, but was involved in forming various Black teams and early attempts to establish national Black leagues. In 1908, when reports emerged that Fowler was dying in destitute circumstances, the Stillwater Daily Gazette recalled that he was “the best all round man on our team” and offered to forward any financial contributions for his support. Fowler died in 1913 and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2022.[22]

In the following years, Stillwater had little interest in another pro league team. When Stillwater was invited to an 1891 meeting to organize a new Northwestern League, the Daily Gazette observed that “Stillwater apparently has had her fill for the present of the league business and those who are apt to have the most direct interest knew nothing of any intention on the part of this city to be represented” in the new league.[23]

1885-1899: High School Football and Other Pastimes

After the collapse of the Northwestern League, the local field was used for a greater variety of sports. In 1885, the former baseball grounds were leased by a Stillwater lacrosse team. The Messenger observed that the team “happens to be composed of the intelligent, aesthetic and social elements of the city’s younger men,” led by two of the city’s physicians. The lacrosse team turned out to be a popular endeavor, with an Independence Day game attracting several hundred spectators. The team was also successful on the field and Stillwater hosted a state championship semifinal game in August.[24]

Following the lacrosse season, the park hosted a September 14, 1885 exhibition match between the “champion female base ball club of the world” and nine selected local players. The traveling team, the Young Ladies Base Ball Club of Philadelphia, had a schedule that would take it across the country from April through October 1885. The game attracted strong local interest: the Daily Gazette noted that it was the reason why all the ball “cranks” (fans) remained at home in Stillwater that day. The newspapers did not report the result of the game. (The women of the traveling team continued on their tour, which came to a sour end the next month when the players were stranded, unpaid, in Lincoln, Nebraska. After a legal complaint by the players, a constable seized the most recent gate receipts and everything else of value in their manager’s possession.)[25]

In 1888, the Daily Gazette reported that there was a local movement to organize a new amateur baseball club to play teams in nearby towns. The newspaper suggested that “no doubt the old grounds can be secured, and if the proper financial inducements are held out, a fence may be erected. Give the boys a chance.” Nothing appears to have happened. The next year, the newspaper made a similar pitch:

The base ball fever has broken out here pretty strong. On Saturday two teams met on the old grounds and played a first class game, developing the fact that there are numerous good players in our city. There is little doubt that the grounds could be secured from Messrs. Staples and Hersey, and subscriptions sufficient secured to erect a fence and a grand stand, the latter on a very moderate scale. The fact that the street cars will be running by these grounds on the first of June make the prospects of patronage much better than ever heretofore. Encourage the boys and we will soon have a good amateur ball club.

In 1890, the newspaper reported that “several well-known gentlemen… are agitating the question of a public park, to be located on the old base ball grounds on the south hill. This property is on the line of the street cars and could be converted into a beautiful place by the outlay of a few thousand dollars.” This idea also went nowhere.[26]

Finally, in 1891, a new baseball team known as the Stillwater Mascots was organized. At first, they played in the existing ballpark. The team’s backers proposed to improve the site as a multi-sport “athletic park” complete with tennis courts and a running track. For its own contribution, the team proposed to supply building materials. The Stillwater streetcar company, whose route ran along Burlington Street, offered to supply the labor. The Hersey & Bean Lumber Company agreed to use of the land without charge. The only thing missing was the consent of 75-year-old lumber baron Isaac Staples. Staples had split off from the Hersey company years earlier but was still partial owner of the land under the ballpark. Staples and the team could not agree on rent, and moreover Staples would not agree to a lease longer than a year. The team could not justify improving the ballpark with such a short lease, and the project appeared dead. Two weeks later, however, the team had reached agreement with Mortimer Webster to lease the “circus grounds” across Orleans Street from the existing park. A new ballpark in “Webster’s Field” was soon constructed.[27]

Though baseball moved across the street from the traditional grounds during the brief Mascots era, the original field continued to be used at least occasionally for purposes such as circuses and national guard drills.[28]

During those years, however, it was clear that the Mascots’ new ballpark was the center of Stillwater baseball. At the start of their second season, 1892, the Mascots secured a three-year lease of the Webster’s Field location. However, landlord Mortimer Webster lost ownership of the land in an 1893 title challenge. Possibly because of this change, the Mascots team seems to have disbanded after their lease ended in 1894.[29]

In the final years of the 19th century, local newspapers only occasionally mentioned baseball played in Stillwater itself, such as amateur games played by high school, Elks Club, North Hill, South Hill, and other teams playing “purely for the fun there is in it.” At the same time, many Stillwater residents rooted for the professional St. Paul Apostles, a Western League team formed by owner/manager/player Charles Comiskey in 1895. During these years, the newspapers contained regular reports of Stillwater residents attending Apostles games in St. Paul. Major changes in baseball would soon bring this era to a close, however. In 1900, the Western League changed its name to the American League and began operating as a major league the next season. With this transition, Comiskey moved his club from St. Paul to Chicago, where they became the White Sox.[30]

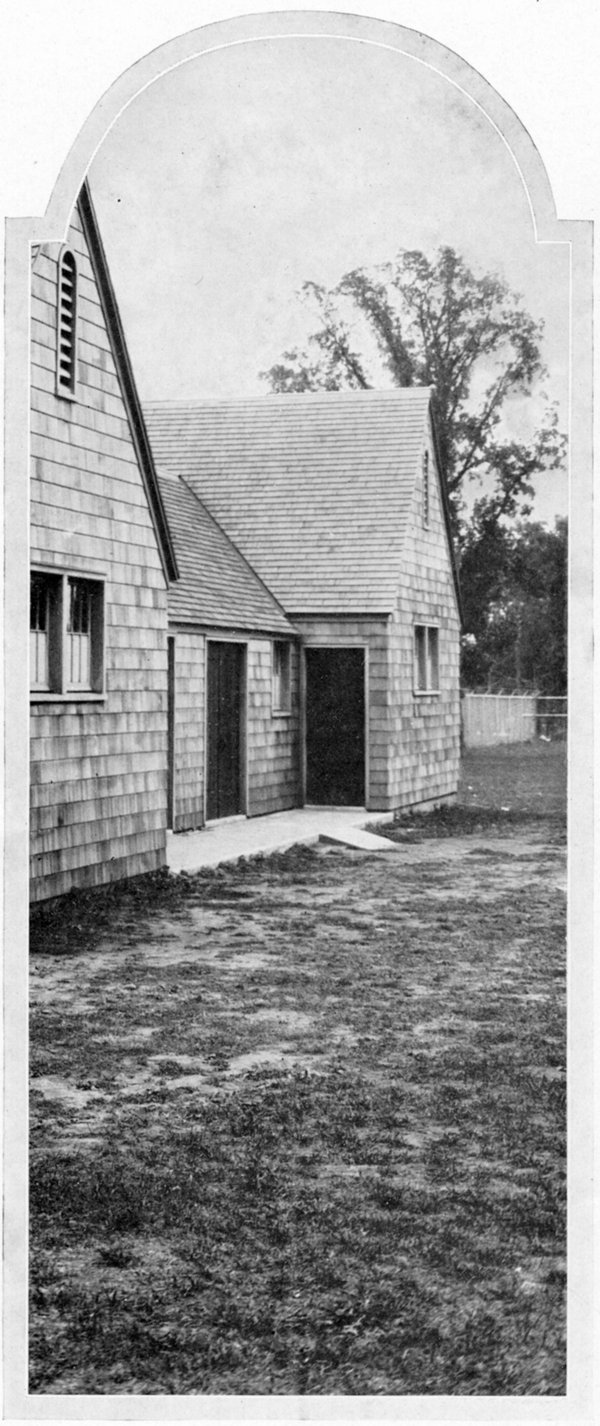

Another development would have a lasting impact on the Stillwater spots scene: high school football. As historian Robert Pruter describes, late 19th century teams typically started as grassroots student-led efforts:

The manner in which high schools, as well as universities, organized football teams was first to establish a club around which an “eleven,” to use the vernacular of the day, would be built. The clubs then issued challenges to other schools to participate in games. There were no teachers, no coaches, and no uniforms. Occasionally, there were schedules and leagues, and there was a crudely laid-out field.[31]

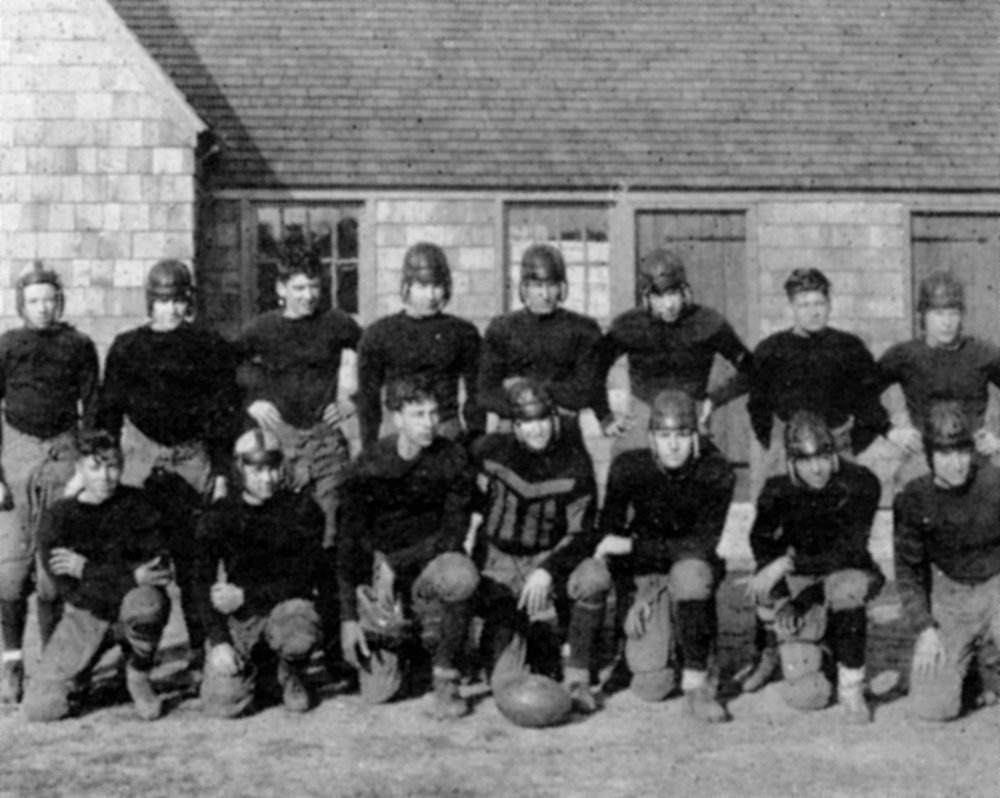

Such was the case in Stillwater. The first known Stillwater High School football game was October 31, 1895, when a student team challenged a squad of “old-timers” who were Stillwater residents who had played football in college or boarding schools elsewhere. The game was played at the “base ball grounds.” It is unclear which ballpark this refers to, but the following year’s games were definitely at the “old” ballpark, which would remain the high school’s home field for the next 71 years.[32]

1900-1926: “Aurora Park” and the Expansion of Local Baseball

The massive changes in major league baseball starting in 1900 created a new opening for Stillwater baseball, which had been largely dormant since the Mascots’ last season in 1894. Additionally, Isaac Staples’ death meant that he was no longer an obstacle to improvements of the original ballpark property. The Stillwater team adopted the sponsored name “Joseph Wolf Brewing Company Club” and played on the original grounds that had been used from 1876 to 1892. The field was not only used by the Wolf club: in mid-July the Gazette observed: “The ball grounds and vicinity were alive with practicing teams last evening. The city has done well over baseball and there are teams galore seeking for contests.” Among these were games between railroaders and bankers, hardware handlers and printers, with additional practice by clubs representing grocers, dry goods handlers, and meat choppers. Other teams in this era were sponsored by specific businesses like Simonet Furniture, playing business-sponsored clubs elsewhere in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Stillwater’s baseball fever was alive and well.[33]

The Joseph Wolf Company Club returned to the field again the next year, making improvements and naming the site Aurora Athletic Park. The name was perhaps intended to flatter Aurora (Staples) Hospes, Isaac Staples’ daughter and one of the heirs who were then in a legal dispute over the field and the rest of their father’s massive estate.[34]

On April 29, 1902, the Daily Gazette reported on the first game at Aurora Park:

It was a delightful day—for Stillwater—and the thousand or more people who thronged the new grounds of the Wolf baseball team yesterday afternoon to witness the opening game of the season were well repaid for their pains… The crowds commenced to gather early and filled the cramped quarters arranged for sittings in no time; those that came later, and there were hundreds, had to stand up. Seats should be arranged to accommodate all who attend the games and the bleachers should be extended clear down to the southwest corner of the grounds…. A number of enterprising gentlemen viewed the game from the surrounding trees and buildings; they appeared to enjoy the game and the sport cost them nothing. One fellow swung a hammock in the top of a study oak and reclined at leisure while he rooted for his favorites…. The attendance was much larger than anticipated and shows the necessity of enlarging the seating capacity at once.[35]

One constituency was less pleased: the Stillwater High School baseball team, which learned it would now be charged rent for use of the new park. The Gazette sympathized with the students’ plight, noting that the team’s fans were mostly fellow students who could not pay more than a dime for admission. Moreover, the students could not approach the business community for support, since many of those businesses were now sponsoring their own amateur teams. The newspaper suggested that it was only reasonable that the students use the field for free, and believed most of the Wolf team’s players had a similar sentiment even if their manager didn’t. It is unclear how the rent question was resolved, but the high school team ended its season by winning the championship.[36]

On Independence Day, a storm delayed a game but did not dampen fans’ enthusiasm: “There was some lively hiking for home, sweet home, yesterday afternoon, from the ball grounds, as the black clouds showed in the north and northwest, but the true fan, the old and reliable boys and girls, stayed right there, and although there was a rainstorm, it was followed by a good game of ball. Nothing but a stroke of lightning or a cyclone will carry the true fan away from a game of ball.” Two weeks after the storm, the Messenger reported approvingly that all of Aurora Park’s seating sections would soon be covered. The following spring, the grounds were expanded and a new grandstand was constructed.[37]

The Aurora Park name generally fell out of use in early 1903, and the grounds became known as Athletic Park. For decades, the park continued to be used for amateur and semi-professional baseball, as well as high school football and other sports. The 1917 Stillwater baseball team won the Interstate League championship. In 1924, Stillwater advanced to the state’s first town team tournament, losing in the final game to the Armour Packers of South St. Paul. The Stillwater Loggers baseball club played from 1933 to 1965 and for a few seasons included Bud Grant, who would later coach the Minnesota Vikings.[38]

1927-1967: “The Athletic Field”: Stillwater Gridiron

The 1920s were a golden era for American sports, driving a dramatic increase in popularity and commercialization. This was seen at all levels, from major league baseball and college athletics down to high school football. During the same era, public high school attendance also expanded to include all youth, not just affluent college-bound students. A larger variety of subjects, activities, and sports were offered to accommodate increasingly diverse students. By the late 1920s, Stillwater boasted an impressive variety of courses and activities, and its Tozer Memorial Gymnasium building had opened earlier in the decade. The school’s outdoor sports facilities, however, were a source of embarrassment to students. Though Hersey and Staples’ lumber company was long gone, the ball grounds were still owned by their numerous heirs—some with shares as small as a 1/64 interest. In July 1927, the Stillwater school board paid the heirs $1,800 to purchase the ballpark site (Block 6, the south half of the present-day field). The board noted that the land had “for some years past been used, jointly with other interests, by the [city school district] as an Athletic Field,” and that acquiring it would serve “the best future interests of the schools and community.”[39]

Once the school district owned the land, the field could be improved. In October 1928, the school board announced a vision for a “model athletic field.” The old baseball grandstand would be demolished immediately, and the park would be enclosed with a new wire fence. Instead of a new grandstand, the district hoped to purchase movable bleachers, allowing the seating to be reconfigured between baseball and football seasons.[40]

Superintendent Gary Smith shared his “model field” vision with the student body during an assembly, and the Arrow student newspaper quickly took up the cause of replacing the old ballpark:

What a field we have!

The fences are worse than rotted; the seats are of no use at a football game; and the space between the field and the fence on all sides but west is entirely too small. A couple of feet more each way would help a great deal.

The businessmen of our city are ashamed of our athletic field—so much that they have offered to help the high school pay for a new one.

If the High school can raise a certain per cent of the money needed for improvements the business men are willing to supply the rest….

The visitors at High school come to the school buildings and are most favorably impressed with the size and beauty of our auditorium, the size and excellence of our gym, the cleanliness of the classrooms and school in general; and then they go out to the athletic field.

All the awe created by the school vanishes and a scornful laugh takes its place.

Why shouldn’t it?

Any school that can afford the type of buildings we have, certainly ought to be able to raise enough school spirit among the inmates to get a crew—two or three, perhaps—to fix that field.

The students are going to make enough money this year so that the businessmen will have to keep their promise and supply the rest; but to get that sum, every pupil will have to do his part.

Perhaps you can’t get on the committee’s or on to teams or among the active workers, but you can get out and advertise (in Stillwater) the need for the new field and get new backers for our plan.

The team would get more kick out of playing if they thought the school cared enough to fix up the athletic field for their games. And the visitors would leave—but, without the grin….

What a wonderful improvement it would be! Dressing rooms for teams at the field, perhaps a couple of tennis courts—we’d love it—a larger football field, a separate baseball diamond, wire fences covered with vines, seats that were movable—those constitute Mr. Smith’s dream field. Compared to that, which could be achieved in a few years, our present field is a nightmare, such as one gets after eating pickles and ice cream.

Let’s all get out and help fix up the field for the honor of the High school.[41]

Funding was needed to realize this vision, and the high school’s students led the way. They aimed to raise $2,000 by staging a theatrical comedy. The Daily Gazette soon offered its support to the students’ efforts:

The ball grounds in Stillwater have long been a disgrace to the city. The fence is in bad condition. The stands are rotting away and the grand stand became so bad recently that it had to be torn down. The field is so rough and in such a bad condition that skilled play is nearly impossible. No provision has been made for dressing rooms. The ball grounds have long been an eyesore to the citizens who live in that neighborhood. Realizing the need for a model athletic field, the students of the Stillwater high school have taken the initiative and are at present raising funds to build a model athletic field. A play will be given November 2 and 3 at the high school auditorium, the entire proceeds of which will go to this athletic fund. Students hope to raise sufficient money so that work can be started immediately on the model field. This is a community project, which the high school students have so nobly sponsored, and as a community project every person in Stillwater should “do his or her bit.” The tickets to the play are one dollar each. Citizens are urged to send their orders immediately to the high school. Do it now![42]

As the play approached, the students announced local businesses’ pledges to the stadium fund, starting with a $25 contribution by First National Bank. A day later, they announced contributions by Rotary Club members including Gazette publisher Ned Easton and Andersen Windows president Fred Andersen. Advertisers in the Gazette used their normal ad space over to promote the play. Meanwhile, student committees fanned out across the community, planning to visit every home in Stillwater, Oak Park, and Bayport to sell tickets for the play and solicit contributions. The play and fundraising drives eventually raised approximately $2,500, surpassing their $2,000 goal.[43]

With the funds raised, superintendent Smith shared his vision with the student newspaper:

There are many things I hope to have on [the athletic field]… a fine football gridiron with tough fine turn, surrounded by a quarter mile track with places around the track for field events such as pole vault, high jump, broad jump, shotput, javelin throw, and hammer throw. I also hope to have movable bleachers on either side of the gridiron. In other parts of the field I hope to have baseball fields, kittenball grounds, tennis courts, volley ball courts, basketball courts, and horseshoe courts. In time I hope to have a field house with ticket sales rooms, equipment rooms, warming rooms and dressing rooms. When all of this is finally accomplished, the whole field will be surrounded by an ornamental iron fence.[44]

To design the facility, the school district turned to University of Minnesota professor Otto Zelner. Zelner agreed to develop concepts for how fields could be laid out using the ballpark grounds recently purchased, or with the addition of the vacant Block 7 to the north. Zelner told the district that based on these conceptual sketches, “it is more apparent than ever that the two entire blocks are most necessary.” The Gazette opined that if these plans were carried out, the new athletic field would “be one of the most modern in the state of Minnesota.” The school board soon purchased the extra land from the Hersey and Staples heirs for another $1,800. Finally, the Stillwater city council vacated St. Louis Street as well as a strip of Fifth Avenue along the east side of the field. These actions combined to establish the athletic field’s present boundaries.[45]

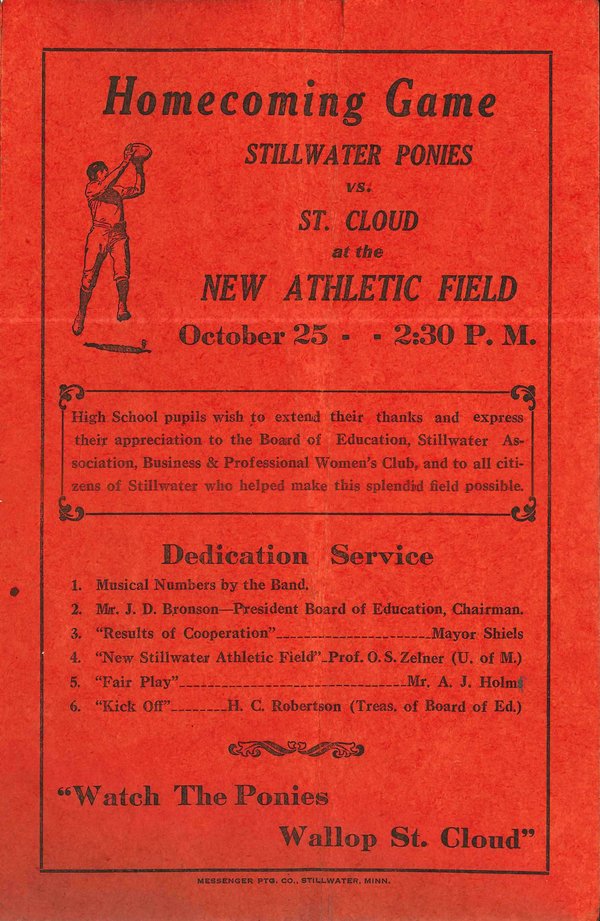

Construction finally started in the summer of 1929, under the direction of city engineer J. Abercrombie. The facility was scaled back somewhat from Smith’s vision, but featured football bleachers for 400, with seating for another 200 on portable bleachers from the high school. Residents were particularly proud of a new field house on the north end, designed by Charles W. Morton of Stillwater’s Consolidated Lumber Company and built with funds raised by Stillwater’s Business and Professional Women organization. The field house was to have a cedar shingle exterior finish, with a brick terrace in front. The interior would feature home and visiting team locker rooms, showers, an office, and tool room. Superintendent Smith told the school board that the field house “is artistic and will serve its purpose splendidly.” Among the field’s amenities, the Gazette especially looked forward to a fence built along the sidelines to ensure that “persons seated in the bleachers will not be bothered by having crowds run back and forth following the ball.” Ultimately, the new stadium cost $4,000, excluding the land. Fundraising provided approximately $2,500, and ticket sales covered the rest.[46]

At the start of October, the Gazette reported that high school students’ enthusiasm for football was “at a high peak…. With the team, one of the strongest in recent years, and with the construction of the field house and the new athletic field nearing completion, students are taking a big interest in the games.” The excitement spread beyond the student body, and the upcoming dedication was “the topic of conversation everywhere in the city.” Downtown took on a “gala appearance” as merchants decorated their storefronts for the occasion, with several stores displaying models of the new field. The Simonet Furniture and Carpet Company was given a prize for best display. Street posts were wrapped with in the school colors, and a large red and black flag was suspended over downtown’s central intersection at Main and Chestnut. The night before the game, students celebrated by building a bonfire and leading a “snake dance” through downtown streets to a pep fest. On the afternoon of the game, a parade of students and alumni wound through downtown to the new stadium—alumni from the class of 1890 won the prize for best float. Finally, after nearly a year of anticipation, the new field was dedicated on Friday, October 25, 1929. A Stillwater victory followed. The day before the dedication, the “Black Thursday” stock market crash had ushered in the Great Depression, but the Gazette observed that “cares of business were forgotten by many citizens as they saw a struggle between two high school teams which will long be remembered.” Stillwater went on to finish the Athletic Field’s first season undefeated.[47]

The Athletic Field was used for high school football for nearly 40 years, including a memorable 1943 season in which Stillwater again was undefeated and outscored its opponents 192-13. High school games moved to a new stadium on Marsh Street in 1967, and the school district demolished the field house and other stadium structures in 2003.[48]

Today, the “Old Athletic Field” continues to be used for the community’s recreational activities, as it has since 1865.

References

-

United States Bureau of Land Management, General Land Office Records, Field Notes for Subdivision of Township 30 N. Range 20 W. of 4th Principal Meridian, accessed at glorecords.blm.gov. Donald Empson, A History of the Hersey Staples Addition Residential Area (Stillwater: Empson Archives, 2000). Washington County, Tract Index to Government Lot 3, Section 34, Township 30, Range 20.

↩ -

“Race Course”, Stillwater Messenger, August 8, 1865, p. 3. “Horse Racing”, Stillwater Messenger, June 6, 1866, p. 1.

↩ -

Quoted in Empson, 54.

↩ -

“Race Track”, Stillwater Gazette, January 24, 1871, p. 4. “Race Track”, Stillwater Gazette, June 13, 1871, p. 4.

↩ -

“Washington County Agricultural Society”, Stillwater Gazette, June 6, 1871, p. 1. “Washington County Agricultural Society”, Stillwater Messenger, February 2, 1872, p. 2.

↩ -

“Washington Co. Fair”, Stillwater Gazette, September 10, 1872, p. 1. “Our County Fair”, Stillwater Messenger, September 13, 1872, p. 4. “Our County Fair Next Week”, Stillwater Messenger, September 20, 1872, p. 4.

↩ -

“Stillwater Park Association”, Stillwater Gazette, October 15, 1872, p. 4.

↩ -

“There will probably be fun”, Stillwater Gazette, July 8, 1873, p. 4. “There is to be a shooting match”, Stillwater Messenger, December 12, 1873, p. 4. “The sportsmen’s clubs of Stillwater and Hudson”, Stillwater Messenger, July 24, 1874, p. 4. “A horse race took place”, Stillwater Gazette, July 29, 1874, p. 4.

↩ -

“Base Ball Club”, Stillwater Messenger, May 29, 1867, p. 1. Stew Thornley, Baseball in Minnesota: The Definitive History (St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2006), 10. “Base Ball”, Stillwater Messenger, September 11, 1867, p. 1. “Base Ball”, Stillwater Republican, June 16, 1868, p. 4. “Base Ball”, Stillwater Republican, October 13, 1868, p. 4. “The base ball club”, Stillwater Gazette, July 15, 1874, p. 4.

↩ -

“Our athletic young men”, Stillwater Messenger, April 21, 1876, p. 4. “B B”, Stillwater Messenger, August 4, 1876, p. 4.

↩ -

Brent T. Peterson and Dean Thilgen, Stillwater: A Photographic History (Stillwater, Minn.: Valley History Press, 1992), 69. “Base Ball”, Stillwater Messenger, October 20, 1876, p. 4. Thornley 15.

↩ -

Cooper, Bailey & Co. advertisement, Stillwater Messenger, July 21, 1876, p. 4.

↩ -

Dan Rice circus ad, Stillwater Messenger, July 27, 1877, p. 1. “By imposing an exorbitant license”, Stillwater Messenger, July 27, 1877, p. 4. “Cole’s celebrated circus”, Stillwater Messenger, May 10, 1878, p. 4. “D.K. Townsend”, Stillwater Messenger, June 14, 1879, p. 4. “W. W. Cole’s circus”, Stillwater Messenger, July 7, 1883, p. 4.

↩ -

“The receipts at the base ball grounds…”, Stillwater Messenger, September 22, 1883, p. 4. “Those of our citizens”, Stillwater Messenger, October 13, 1883, p. 4.

↩ -

Thornley 16-17. “The following is a list of…”, Stillwater Messenger, March 22, 1884, p. 4. Dan Cagley, “Bud Fowler and the Stillwater Nine, 1884”, in Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota, edited by Steven R. Hoffbeck (St. Paul, Minn.: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 16.

↩ -

Thornley 17. Cagley 14. “About Bud Fowler”, National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/fowler-bud, accessed 8/18/2024.

↩ -

“Base ball enthusiasts”, Stillwater Messenger, February 23, 1884, p. 4. “Before the league base ball games are inaugurated”, Stillwater Messenger, April 19, 1884, p. 4.

↩ -

“Stillwater News”, St. Paul Daily Globe, June 2, 1884, p. 5.

↩ -

“Stillwater News”, St. Paul Daily Globe, June 3, 1884, p. 6. “A telegraph line”, Stillwater Messenger, June 7, 1884, p. 4. The lots across Fifth Avenue, Lots 10-18 of Hersey, Staples & Co.’s addition, were still owned by the Hersey and Staples families in 1884 and likely remained vacant.

↩ -

Thornley 17-21. Brian McKenna, “Bud Fowler”, Society for American Baseball Research, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/Bud-Fowler/, accessed 8/18/2024.

↩ -

1884 Stillwater City Directory. W.H. Humphrey in 1885 Minnesota State Census for Stillwater.

↩ -

Thornley 21. McKenna.

↩ -

“Stillwater Not In It”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, January 29, 1891, p. 3.

↩ -

“The Stillwater lacrosse club”, Stillwater Messenger, May 15, 1885, p. 4. “The home lacrosse club”, Stillwater Messenger, June 20, 1885, p. 4. “Last Saturday the eagle…”, Stillwater Messenger, July 11, 1885, p. 4. “The home lacrosse club”, Stillwater Messenger, August 29, 1885, p. 4.

↩ -

“Base Ball”, Donaldsonville (La.) Chief, April 4, 1885, p. 3. “A female base ball club”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 14, 1885, p. 3. “Facts Before the Funeral”, Omaha Daily Bee, October 24, 1885, p. 5. The traveling team was not named in the Stillwater articles, but a Red Wing game earlier in the month used nearly identical local advertisements, and the St. Paul Daily Globe noted the name of the Philadelphia club in stories about the game there.

↩ -

“A number of our young base ball enthusiasts…”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 26, 1888, p. 4. “The base ball fever”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, April 23, 1889, p. 4. “A Public Park”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 2, 1890, p. 3.

↩ -

“Interesting Sporting Event”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 30, 1891, p. 3. “To Build a ’Ball Park”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, June 5, 1891, p. 3. “That Athletic Park Scheme”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, June 5, 1891, p. 4. “The Stillwater club is negotiating…”, Stillwater Messenger, June 5, 1891, p. 4. “Arrangements are nearly completed…”, Stillwater Messenger, June 20, 1891, p. 4.

↩ -

“Short Stops”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, July 2, 1891, p. 3. “Ringling Bros.’ united shows…”, Stillwater Messenger, August 20, 1892, p. 4.

↩ -

“Messrs. D. J. Kennedy and D. J. McCarthy…”, Stillwater Messenger, February 6, 1892, p. 4. “An Important Decision”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, November 6, 1893, p. 3.

↩ -

Thornley 29-30. “Several of the base ball players are talking….”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, April 27, 1895, p. 3.

↩ -

Robert Pruter, The Rise of American High School Sports and the Search for Control: 1880-1930 (Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press, 2013), 18.

↩ -

“Foot-ball”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 30, 1895, p. 3. “The first team of the high school….”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 16, 1896, p. 3.

↩ -

“Base Ball Tomorrow”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 19, 1900, p. 3. “On the Diamond”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, July 13, 1900, p. 3. Peterson and Thilgen 70.

↩ -

“Baseball Plans”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, April 4, 1901, p. 3.

↩ -

“Heart Disease Finish”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, April 29, 1901, p. 3.

↩ -

“High School Items”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 1, 1901, p. 3. Peterson and Thilgen 70.

↩ -

“There was some lively hiking…”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, July 5, 1901, p. 2. “Aurora ball park will have a covering…”, Stillwater Messenger, July 27, 1901, p. 4. “Baseball Begins”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, March 14, 1902, p. 3.

↩ -

Brent T. Peterson, Stillwater: The Next Generation (Stillwater, Minnesota: Valley History Press, 2004), 137-139. Thornley 125-127. Peterson and Thilgen 70.

↩ -

Pruter 173. “Homecoming of S.H.S. with Opening of Gym”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, March 20, 1923, p. 1. “Help Fix Up the Field for Honor of School”, Stillwater High School Arrow, October 8, 1928, p. 1. Stillwater City School Board, Minutes 7/12/1927 and 12/13/1927, box 129.J.9.1B, Minnesota Historical Society.

↩ -

“Ball Grounds To Be Changed”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 13, 1928, p. 1.

↩ -

Arrow, October 8, 1928.

↩ -

Stillwater City School Board, Superintendent’s Report to Board 10/8/1928, Minnesota State Archives, box 129.J.9.5B, Minnesota Historical Society. “The ball grounds in Stillwater have long been a disgrace…”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 27, 1928, p. 3.

↩ -

“Local Men Aid Athletic Fund”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 24, 1928, p. 1. “More Contributions Are Made for Athletic Fund”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 25, 1928, p. 1. Advertisements, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 26 and 31, 1928, p. 4. “Splinterville Otto’s Dividends”, Stillwater Arrow, November 19, 1929, p. 2. Stillwater City School District, Superintendent’s Report to Board 12/9/1929, Minnesota State Archives, box 129.J.9.5B, Minnesota Historical Society.

↩ -

“Mr. Smith Interviewed”, Stillwater Arrow, December 3, 1928, p. 2.

↩ -

Stillwater City School Board, Minutes 4/4/1929, Minnesota State Archives, box 129.J.9.1B, Minnesota Historical Society. Stillwater City School Board, Superintendent’s Reports to Board 12/10/1928, 3/9/1929, 4/8/1929, Minnesota State Archives, box 129.J.9.5B, Minnesota Historical Society. “Athletic Field Here May Cover Two Big Blocks”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, April 10, 1929, p. 1. “Council Approves Terminal Plans”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 22, 1929, p. 1.

↩ -

Stillwater City School District, Superintendent’s Reports to Board 10/5/1929 and 12/9/1929, Minnesota State Archives, box 129.J.9.5B, Minnesota Historical Society. “50 Out for H.S. Eleven”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 5, 1929, p. 6. “Work Begins on Field House”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, September 13, 1929, p. 6. 1927-28 Stillwater City Directory. “Field House Drive to Open Thursday”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 2, 1929, p. 1. “Athletic Field of High School Is Dedicated”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 25, 1929, p. 1. “Ponies Win as Athletic Field is Dedicated”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 26, 1929, p. 1.

↩ -

“Ponies in Excellent Condition for Game with St. Cloud Here Friday”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, October 22, 1929, p. 2. Daily Gazette, October 26, 1929. “With Backs to Wall Stillwater Holds Red Wing to Scoreless Tie”, Stillwater Daily Gazette, November 12, 1929, p. 2.

↩ -

Peterson 131. “Pony Gridders Play Packers Here Today”, Stillwater Evening Gazette, September 14, 1967, p. 2. “District in clear for razing building”, St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 23, 2003.

↩