North Hill Burying Ground

Stillwater's First Cemetery

The first Stillwater burial grounds were established in 1846 at the top of the North Hill. Though used as a cemetery, the land owned remained owned by John McKusick of the Stillwater Lumber Company.[1]

When McKusick engaged a surveyor to officially lay out Stillwater two years later, the street grid placed the cemetery north of Laurel Street, between Second and Fourth Streets. The 1870 Bird's Eye View map of Stillwater depicts the cemetery north of the established city neighborhoods, and just south of a large ravine. It likely had a view of the St. Croix River.

One memorable funeral was that of the first Stillwater man to die in the Civil War, Captain Gold Curtis, on August 2, 1862:

At two o’clock the remaining members of the old Stillwater Guard, together with a few returned soldiers, under the command of Capt. Bromley, preceded by the Great Western Band, formed in their Armory and proceeded as an escort to the Masonic fraternity and a large concourse of citizens, to the late residence of the deceased. The procession being formed in the usual order, under direction of Chief Marshal D. A. Bronson, the line of march was taken up. We have seldom witnessed a more solemn or impressive scene. The mournful dirges of the band, the low and measured tread of the soldiery with reserved arms and sheathed bayonets, the emblems of mourning displayed by the various associations represented, the deep sorrow which every one in the immense procession felt and expressed—all conspired to render the occasion deeply impressive.

The religious exercises were conducted by Rev. Mr. Bull and Rev. Mr. Howell, at the Myrtle Street Church. The oration by Rev. Mr. Bull was one of his finest productions. The placed the cause of the war face to face with the lamented dead before him, and in burning words charged the responsibility of the death of Captain Curtis and tens of thousands of others of our brothers and countrymen directly upon the rebel traitors and their sympathizers.

The rites of burial were conducted by the Masonic Order in the usual manner. The rites were conducted by Worshipful Master, L.E. Thompson, joined by the entire brotherhood. It was an impressive scene—the sundering of earthly ties and the surrendering to the Great Architect at that quiet sun-set hour, of a brother and a friend. These impressive exercises completed, the military paid their last honors to a brother solider, by firing three volleys over his grave; when, to more inspiring music and with arms equipped for battle, the military and various associations represented left the grounds and repaired to their various halls.[2]

The burial ground was created out of necessity when Stillwater was a small village, and it was less formal than many modern American cemeteries. A resident wrote to the Stillwater Messenger in 1858, deploring the cemetery's condition:

Who has charge of our burial ground in this place? and whose business is it to see that any order is maintained there, in the resting place of the dead? A more pitiable sight, there is not any where in our city, than the present condition of our burial ground. The ground was never laid out into lots, no streets or paths were ever reserved, and now it is impossible to drive through the ground without coming into contact with graves. These graves, too, are not parallel with each other, but lie at all angles, in the most perfect confusion and disarrangement. The graves have been dug, just where it seemed the easiest to dig, and the freest from roots, without any reference to other graves, or the way of approach to them; and then the bushes have been cut, here and there, just as room might be needed for the coffin to reach the grave. The next person then coming to dig a grave, puts it in this temporary path, that was opened, and thus the filling up of the yard continues. Who is responsible for these? It is a disgrace to our city as it now is.

There are many strangers buried here, and afterwards, friends arrive, either to remove the bodies, or to erect stones at the graves. But such is the disorder of every thing connected with the ground, that the graves cannot be identified either by those that dug them, or by the local minister that officiated at the funeral service.[3]

Eight years later, North Hill burying ground was replaced by new cemeteries. In 1866, Catholics purchased land for St. Michael's Cemtery in Baytown Township. The following year, Fairview Cemetery was established just south of Stillwater.[4]

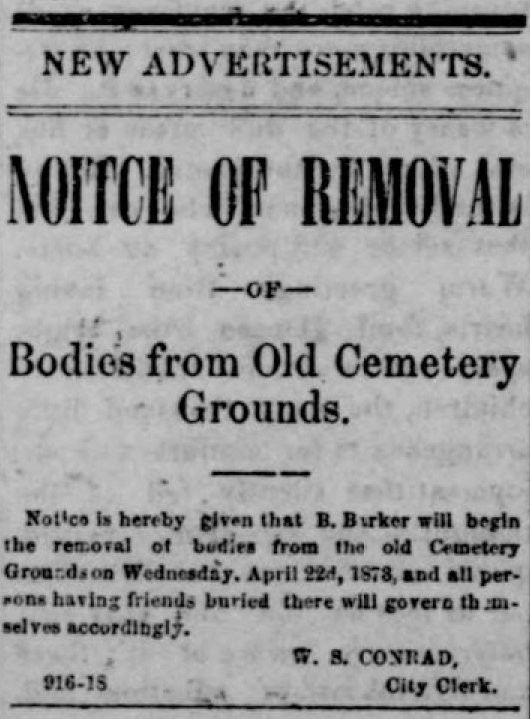

In theory, families were to arrange to relocate their relatives' remains to one of the new cemeteries. However, this doesn't seem to have happened by 1873, and McKusick may have been anxious to sell land that was now in the center of the city. With special permission from the state legislature, the Stillwater city council engaged a contractor to move the remaining remains. On April 11, the city placed a newspaper ad announcing the removal of the bodies and admonishing friends of the deceased to "govern themselves accordingly."[5]

The day after the notice appeared in the newspaper, John McKusick sold the west portion of the cemetery to the Stillwater school district, for the construction of Lincoln School. The next summer, he sold the east portion of the cemetery to Dwign M. Sabin, a state senator and manufacturer. Finally, McKusick deeded the rest of the cemetery land for the city, allowing the extension of Third Street and creation of School Street.[6]

Not all of the bodies from the old disorganized burial grounds made it to the new cemeteries. In 1910, a crew excavating for a gas main under Third Street unearthed the skeleton of an unidentified young woman. Six other graves contained remnants of decayed caskets, but no bones. The Daily Gazette relayed some history:

"Resurrection" Bernard Barker, as he was alluded to, had the contract 37 or 38 years ago to move bodies from the old to the new cemeteries, at the price of $8 each. He was a character in his day, and was given the sobriquet of "Resurrection" Barker because of his work of exhuming and re-interring bodies.

In those days some graves were not marked and it is now evident that Barker's work of moving bodies was not entirely thorough. A few years ago a skeleton was found in the Lincoln school yard when digging to set a fence post.[7]

— Matt Thueson

Matt Thueson is a member of the Stillwater Heritage Preservation Commission.

References

-

Folsom, W.H.C, Fifty Years in the Northwest (Saint Paul: Pioneer Press Company, 1888), 410.

↩ -

"Funeral Obsequies of Captain Gold T. Curtis", Stillwater Messenger, [probably August 5], 1862. Folsom 429.

↩ -

"Our City Cemetery", Stillwater Messenger, March 9, 1858, p. 2.

↩ -

S Deeds 389, R Deeds 512, Washington County.

↩ -

"Notice of Removal," Stillwater Messenger, April 11, 1873.

↩ -

V Deeds 545, X Deeds 272, X Deeds 518, Washington County.

↩ -

"Old Graves are Found", Stillwater Daily Gazette, May 5, 1910, p. 2.

↩